The purple finch designation was supported by the state Audubon Society and civic groups. A similar effort to make the state bird the New Hampshire hen failed to garner sufficient support. Monahan, a legislator from Hanover and a Dartmouth College forester, sponsored and championed the bill. In 1957, Governor Lane Dwinell signed legislation designating the species the official state bird of New Hampshire. The purple finch has a special relationship with the Granite State. Loss of suitable habitat as a result of a changing climate is of particular concern.

Other threats to purple finches include window collisions, predation by cats, and climate change. The female incubates eggs for about two weeks, and both parents feed the chicks.Īccording to American Bird Conservancy, purple finch populations are threatened by habitat loss and competition from house finches, a species native to the western U.S.

Purple finches may also nest on Christmas tree farms or near more developed areas. Located as low as a few feet and as high as 60 feet off the ground, these nests are made of grass, rootlets, and twigs, and are often concealed by bunches of needles. The eggs are protected by a cup-shaped nest, which the female builds in a conifer. Nesting takes place in late spring and early summer. These irruptions send purple finches on a roving aerial quest for food. When conifer seeds are lacking in northern areas, purple finches will travel short distances to forage. These birds will also consume flowers, buds, and small fruits, as well as beetles, caterpillars, and aphids. Natural foods include the seeds of elms, maples, sweet gum, sycamore, and aspen. Purple finches spotted in the Northeast during winter may include year-round residents that don’t migrate, birds that breed in more northern areas and are passing through to wintering grounds in the southern and central United States, and short-distance migrants following food sources. Bird feeders, especially those stocked with black oil sunflower seeds, may attract these birds to backyards. However, during winter they may also appear in swamps and suburban areas. Purple finches in our region breed mainly in coniferous and mixed forests.

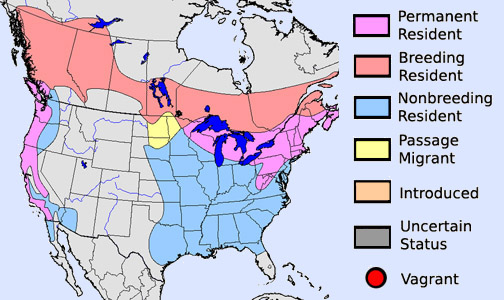

The purple finch is a year-round resident of New England, New York, and most of Pennsylvania, as well as the Great Lakes region and the Pacific Northwest.

While males may be confused with house finches, the latter are not native to the East Coast and lack the pizazz of the purple finch. Purple finches measure roughly 5 to 6 inches in length and sport conical, seed-crushing beaks. As biologist Chris Earley noted in his book, “Feed the Birds,” the male purple finch has “been described as being dipped in raspberry juice.” The female is brown with white streaks and a white throat. The male purple finch ( Haemorhous purpureus) is pink-red with a touch of brown. Perhaps the most vivid remaining species is the purple finch, which occurs in northeastern forests year-round and is a winter visitor to bird feeders. The departure of ruby-throated hummingbirds, Baltimore orioles, migratory woodpeckers, and numerous warblers doesn’t leave us entirely without striking birds, however. In September, as summer yields to fall, most of the colorful birds that breed in our region during spring and summer head south for warmer locales.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)